Careers, diversity and productivity

This post links three interesting events/publications from the last week.

First, I attended an invigorating conference on Women in Economics at Warwick University. The organiser Stephanie Paredes Fuentes and her team did a great job in bringing students from many universities (and countries – a very international group) together to discuss some of the challenges facing women doing economics – one of the very few subjects where men still outnumber women.

I was present only for the panel session on the Sunday. Luisa Affuso, chief economist at Ofcom, graphically described some of the severe challenges she had faced as a pioneer in her profession, and this led to some discussion of what a ‘career’ now looks like and might look like in the future. I brought the gloomy news of the prospective 50-year span that faces people about to start their working lives. In that more extended context, rethinking what we mean by a career becomes all the more important. This is especially the case as the latest data shows the gender pay gap is almost flat until the late 30s, and then rises sharply.

Most of the students, naturally, were more concerned with overcoming barriers to their immediate progress into work than with the second half of their working life . (These barriers include, as I was told over coffee, the attitudes of some male students who had entered economics in order to become investment bankers, and who according to my informants tended to exhibit what might be called an excessive degree of self-confidence.) But a recent report from the Resolution Foundation on working hours trends makes me think again how important it is to be aware of patterns over the life course.

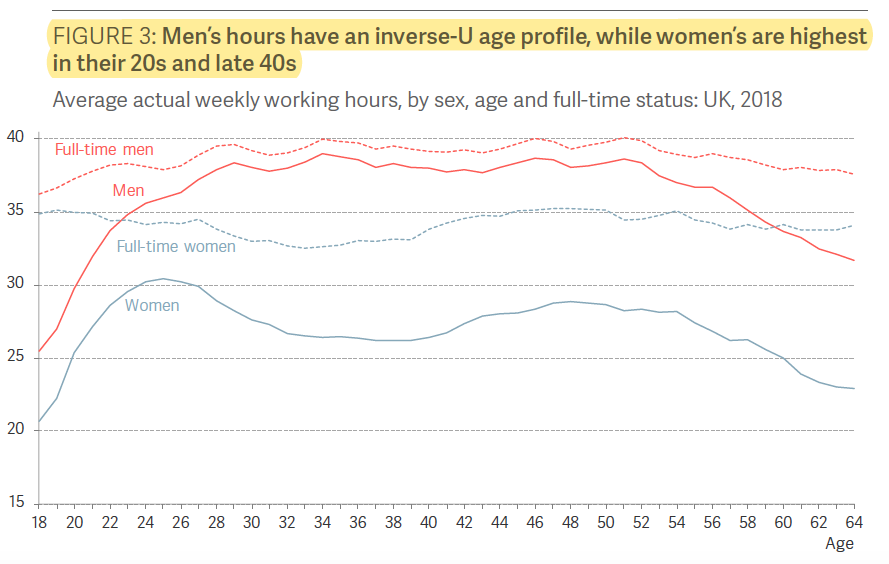

The overall message from the RF report is that the long-run decline in working hours has stalled since the financial crisis of 2008. But there is a wealth of information on overall working patterns. Women’s hours vary over the life course much more than men’s. As the RF’s Fig 3 shows, they have a kind of bi-modal pattern, highest in their mid-20s, dropping and then rising again to a new peak in their mid-50s. Men’s hours rise steadily, but don’t vary much throughout the 25-54 period.

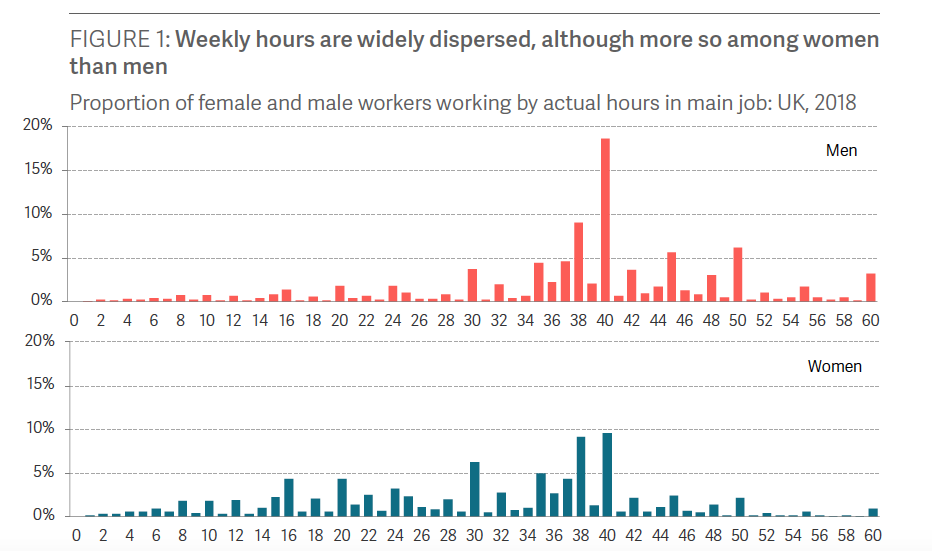

Secondly, there is far greater diversity in working time in the UK than in most comparable countries. As the RF’s Fig 1 shows, this is mainly because of the pattern of female employment.

Most particularly, part-time working – almost unknown before WW1, and only 5% of all work in the 1950s – tripled in the post-war period and has now reached nearly 30% of all work. It has gone up steeply amongst men: in 1979 only 7% of men worked part-time, by 2009 it was 19%.

Where does this take us? For me there are 3 key points:

a. Notions of a professional career have not caught up with these trends. This is largely because although there are many more men working part-time, they tend to be in less professional occupations. Highly qualified men are actually working longer hours than they used to. There is a striking contrast with earlier times, when greater leisure was a sign of status.

b. ‘Part-time’ has become too baggy a category to do justice to what is going on. The simple binary divide lumps too much together. I’ve made this point before, and recognise all the difficulties involved in changing categories, but it is increasingly unsatisfactory – and increasingly important when it comes to women’s careers. Until non-full-time working patterns are given proper attention, progress will be slow.

c. The life course approach is crucial. Just reflect on that growth in labour market participation of people aged 65+: it has more than doubled, from 5.1% at the beginning of the century to nearly 11% today. The curves shown in Fig 3 above will have to be extended – and they will change shape. In this context, women’s greater willingness to learn will take on a new value.

My third event was the launch at the RSA of a collection of essays on productivity. It contains many pithy and useful contributions; but I missed anything on the implications for productivity on the underutilisation of women’s competences. This, surely, is an area that the budding female economists could usefully focus on. Just a suggestion…