Extreme PP: the Korean case

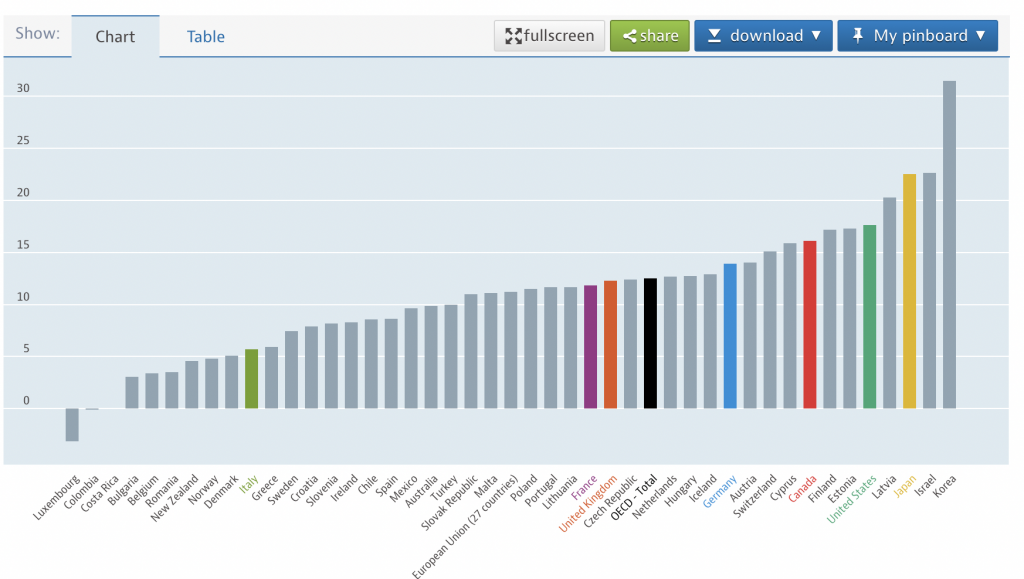

When I wrote the PP book, now nearly five years ago, South Korea was already the extreme example of the Paula Principle. On the education side young Korean women had shot up the OECD table of tertiary level achievement; but at work their qualifications gained little recognition, and the gender pay gap remained one of the biggest.

A startling article from the New York Times reports on a wave of anti-feminism. Young male Koreans are turning their anger on women, who they see as depriving them of their life chances – in spite of the evidence that in their country above almost every other young women are unable to convert their educational success into professional rewards.

“South Korea has the highest gender wage gap among the wealthy countries. Less than one-fifth of its national lawmakers are women. Women make up only 5.2 percent of the board members of publicly listed businesses, compared with 28 percent in the United States. And yet, most young men in the country argue that it is men, not women, in South Korea who feel threatened and marginalized. Among South Korean men in their 20s, nearly 79 percent said they were victims of serious gender discrimination.”

Street marches by groups such as Man on Solidarity, public vilification of prominent women and attacks on the Korean Ministry for Gender Equality and Family are part of the picture.

Some of the reasons for the anger, even hatred, exhibited by Korean men are common to many OECD countries. A general decline in stable career opportunities, housing shortages and growing inequality are widespread. Other factors may be specific to Korean culture; I’m not familiar enough to comment on these but Hyun-Joo (not her real name) was one of my PP interviewees. In Korea her paternal grandmother had been a highly reputed sculptor, and her parents academics. She had gained a PhD in the UK and returned to the Seoul National University. But the profile of the faculty was chauvinist and nationalist.

“We had a faculty meeting. It was held in what we call a ‘dog’s restaurant’ (ie where dog meat is served). I don’t eat meat, and I’m a non-drinker. They all wanted me to drink – I had to walk out. But I’m unusual – other female assistant professors are adjusting to that culture.”

In any case, there are warning signs here of what might be a more widespread and dangerous underlying tension: between the legitimate claims of educated women to better careers, and more generally to greater personal autonomy; and the resentments of younger men who face an uncertain future and find a primeval target for their anger.

Age and gender intersect. Hyun-Joo’s account describes one aspect, but an alarming different generational divide appears, as young men blame their predecessors. The NYT piece quotes Oh Jae-ho, a researcher at the Gyeonggi Research Institute in South Korea:

“Men in their 20s are deeply unhappy, considering themselves victims of reverse discrimination, angry that they had to pay the price for gender discriminations created under the earlier generations.”

It’s difficult to think what the reactions might have been if Korea had been more successful than it has been in reducing the gender pay gap. But in any case it’s an ominous warning sign of pushback against gender equality, especially when aligned with intergenerational tensions.