LRB’s power pieces

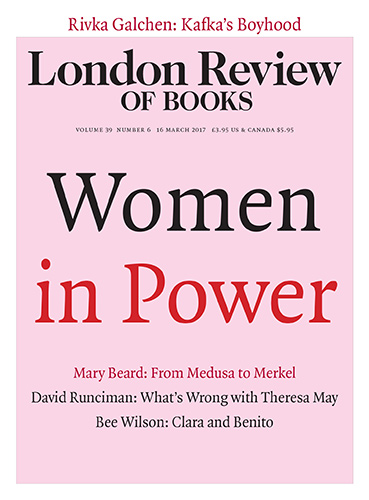

Two excellent PP-relevant pieces in a recent issue of the London Review of Books.

One is a review by David Runciman of a book on Theresa May which sums up her trajectory to power in a way that really helped me get a fix on the PM’s outlook and attitude. Especially telling is the contrast he draws between May and David Cameron, at several points in their political careers. Cameron is

…all posh-boy charm and insouciance, flying by the seat of his pants with the aid of his network of well-connected chums. May is earnest and diligent, apparently less opportunistic and more willing to assess things on their merits.

And you can’t get a much crisper characterisation of their differences than this, exactly illustrating PP factor 3:

He was the essay crisis prime minister. She is the do-your-homework prime minister.

The second piece is by Mary Beard. In a lecture on ‘Women in Power’ she says she wants

to think harder about how and why the conventional definitions of ‘power’ (or for that matter of ‘knowledge’, ‘expertise’ and ‘authority’) that we carry round in our heads have tended to exclude women.

Beard goes on, as one would expect, to explore this by reference to classical literature and myth. She includes a penetrating analysis of how the Medusa story has been visually depicted, climactically in a representation of Perseus-Trump brandishing the head of Medusa-Clinton – the ‘hero’ slaying the demon woman.

We get into PP-relevant territory when Beard questions the focus on what she calls ‘high end’ power, the kind of analysis which concentrates on glass ceilings, top politicians and CEOs. She says

I don’t think this model speaks to most women, who even if they aren’t aiming to be president of the US or a company boss, still rightly feel that they want a stake in power.

And in occupational success. Several of my interviewees said exactly this about the image of the glass ceiling: they felt it had nothing to do with them, but they still wanted their careers – and their expertise – taken seriously. Beard picks up the theme later:

You can’t easily fit women into a structure that is already coded as male; you have to change the structure. That means thinking about power differently. It means decoupling it from public prestige. It means thinking collaboratively, about the power of followers, not just of leaders.

Again, this seems to me to apply very directly to the workplace as well as the political forum. Thinking collaboratively (the diametric opposite of groupthink) is a very valuable organisational asset, as well as a political advantage. Which competences are valued and rewarded, and who decides on the rating system that defines the values and allocates the rewards? These are not formulaic issues, but ones of power.