Malala working for free(dom), and negotiations

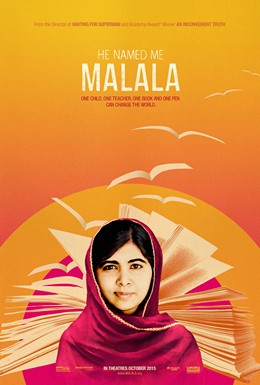

I went with my daughter yesterday to see the film He Named Me Malala. It’s an extraordinary mix: the unique, improbable story of Malala’s path to the Nobel Prize (with detail of the titanium plate they had to insert into her head after the shooting, and all the efforts to recover the use of her muscles), and the her apparent capacity to maintain the life of an ordinary schoolgirl with two brothers, in a Birmingham home. I found it moving, and for once inspirational is an appropriate description.

The film is founded on the way her father encouraged her, and other girls, to carry on with their schooling. He poses the question of whether this was the right thing to do, knowing now the danger it placed her in. She answers him by saying that what he did was to give her her name; she made the choices after that. It’s a remarkable relationship of trust and pride.

Malala crusades across the world for girls’ education. We see her teaching in an African classroom; she uses the whiteboard confidently to explain to the children (boys and girls) about Pakistan’s economy and geography. At the other end of the spectrum, she lectures, equally confidently, to the UN general assembly. She has a natural flair for rhetoric.

Of course the global task is to achieve gender parity at school level. This is where the huge inequalities lie, with female literacy levels still way behind. But what happens when parity is reached? We know, as surely as anything, that girls will carry on to outdo boys – in the educational sphere. And then?

Which brings us to Working for Free: yesterday was the day where the gender pay gap kicks in, so that from now to the end of the year women, on average, are in a sense working for nothing. Naming the day is a brilliant way of bringing home the inequalities of the labour market. Even when women are equally – or, as they increasingly are, more highly – qualified, the material pay-offs don’t seem to be there. So what to do?

I’ve been reading quite an old book called Women Don’t Ask, by Linda Babcock and Sara Laschever, which details all the research that shows how women don’t negotiate deals for themselves at work. This very much what underpins PP factor 3: psychological factors, and lack of confidence in their abilities and experience. The book focusses on enabling women to negotiate their way to better deals – not only in pay and promotions, but also working hours and other aspects of the job. It does a useful job in covering the different angles, and in showing women ways of upping their negotiating capacity.

But now here’s a challenging post from Penelope Trunk, on why women shouldn’t bother negotiating. She’s just telling it like it is, but says she expects to get clobbered for it, and the responses prove her right. For me the interesting question is not so much how to enable women to negotiate more – though they often should – but how to operate on the other side; in other words, how to change the reward systems so they don’t depend as much on people’s capacity to ask, insist, bang the table. But I’d love to hear Malala’s views on negotiation.