Net-zero economy: a competence challenge

I’ve been reading a most stimulating report from Nesta on preparing the UK workforce for the transition to a net-zero economy. The report offers a new approach to categorising employment sectors, defining them in terms of two dimensions: their current emissions, and the level of their commitment to a transition.

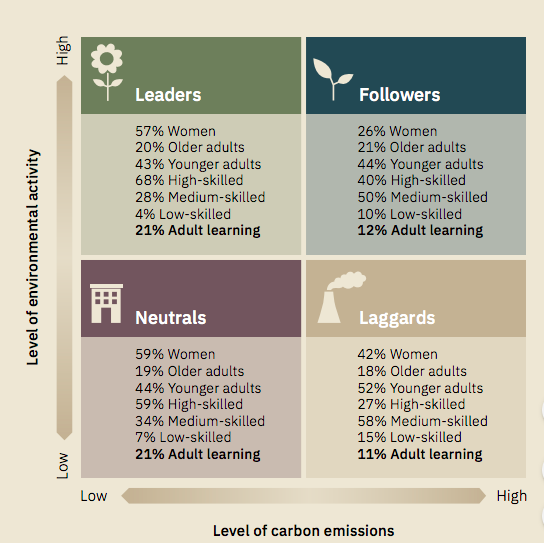

This generates a fourfold typology. The green sector covers ‘leaders’ and ‘neutrals’; the brown sector covers ‘followers’ and ‘laggards’, defined as follows:

— Leaders: Industries in this category are the most eco-friendly, as they do not produce high levels of carbon emissions and are involved in activities that directly protect the environment across the economy: professional, scientific and technical activities; education; arts, entertainment and recreation; and public administration and defence, and compulsory social security.

— Neutrals: Industries in the ‘neutral’ category produce low levels of carbon emissions but are not involved intensively in activities that directly protect the environment: financial and insurance activities; real estate activities; human health and social work activities; and administrative and support service activities

— Followers: Although they are producing high levels of emissions, followers are also involved in activities that are intended to protect the environment and could thus create green jobs: agriculture, forestry and fishing; manufacturing; electricity, gas and water supply; construction; and other services.

— Laggards: Industries in this category produce high levels of carbon emissions and are not involved intensively in activities aimed at protecting the environment: mining and quarrying; wholesale and retail trade, and repair of motor vehicles and motorcycles; transportation and storage; and accommodation and food service activities.

The distribution of total employment is fairly equal across all sectors, ie each sector has 20-30% of the workforce. The classification into just four categories inevitably produces some quite heterogeneous categories. Where it gets interesting is the breakdown of employee categories within those sectors:

It’s probably not a surprise – but nevertheless mildly gratifying – that the proportions engaged in adult learning are higher for the green than the brown sector. It’s also predictable that women are the majority in the Leader occupations. They figure more amongst the Laggards than the Neutrals, mainly I guess because the former category includes accommodation and food services. The skill distribution is very evidently lop-sided, with a far higher proportion of high-skilled employees amongst the Leaders.

What this should help us towards is not just a better grasp of how different occupations can be ranked, in addition to conventional classifications (on which see this v interesting paper by my friend Ian Gough, which confronts issues of value: what kinds of activity add value – and which destroy it). The Nesta paper provides a lens through which we can get a clearer picture of the educational challenges that necessarily accompany efforts to move towards a greener economy.

They recommend, sensibly,

- programmes which build on eco-job analyses;

- funding for training to enable people to make the transition out of brown sector jobs, with necessarily a strong regional/local focus;

- paying due attention to non-traditional forms of adult learning

- measures to upgrade eco-friendly innovation should all include a prominent skills component. I like the proposal for a single organisation to lead this approach.

What is also clear, though unremarked on in the paper, is that it will require a particular effort to enable low- and medium-skilled men to make a successful transition out of the laggard and follower sectors. That is an interesting challenge – I wonder who will be taking it up.

More directly related to the Paula Principle, a recent Social Europe report by Irene Giner-Reichi from Austria deals with the gender implications of a transition to a green economy. She deals in part with the well-known need for more women in STEM subjects, but also points specifically to the role the the business world can play in boosting female employment in green industries. I found this an interesting example of a positive investment initiative:

the Turkish firm Polat Energy recently took out a $44 million ‘gender loan’ to finance the construction of Turkey’s largest wind farm. The loan terms will improve if the company demonstrates further progress toward gender equality relative to an initial baseline.

She concludes:

As countries everywhere embark on ‘building back better’ after Covid-19, energy-transition strategies should be a key element in any stimulus package. And they will be far more likely to succeed if women play a central role.