OECD says it: rebalance the system in favour of FE

My former colleagues at OECD have just produced an excellent report which should disturb, and which deserves really wide discussion – especially as I agree wholeheartedly with one of their major, and radical, recommendations.

Building Skills for All: A Review of England looks at the problem of low skills. A familiar issue, you may see – haven’t we heard it all before. Well, try this:

“Around one in five young English university graduates can manage to read the instructions on a bottle of aspirin, and understand a petrol gauge, but will struggle to undertake more challenging literacy and numeracy tasks.”

This is based on PIAAC evidence – an international survey based on direct testing of people’s competences (Hence the aspirin bottle and petrol gauge – real-life tasks sued for the tests). These are graduates in the standard English sense – people with degree qualifications. Makes you think, whether or not you’re a Daily Mail reader.

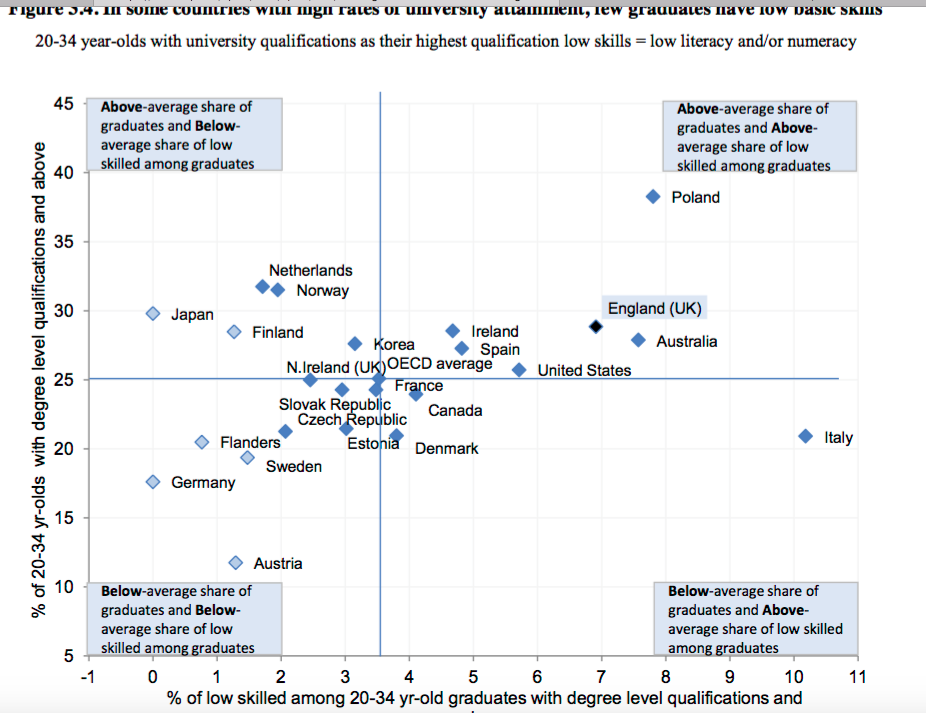

England is in the top right quadrant: high proportions of graduates, but unusually high proportions of them with low skills. Not where you want to be.

I’m not happy about that. But I am happy about the conclusions that the OECD draws:

“Those with low basic skills should not normally enter three-year undergraduate programmes, which are both costly and unsuited to the educational needs of those involved, while graduates with poor basic skills undermine the currency of an English university degree. These potential entrants should be diverted into more suitable provision that meets their needs. Such students need postsecondary alternatives that will address their needs andtackle basic skills. Such alternatives need further development in England. Resources diverted from university provision should be redeployed, particularly in the FE sector, to support this.” (p16)

Some of us have been arguing for some time for such redeployment, though not on the basis of the evidence that the OECD have now been able to adduce. Alison Wolf is one who has powerfully pointed out the almost grotesque imbalance in the way the FE sector is treated compared to HE. I know that my former university colleagues (yes, I’ve been around, so have quite a variety of former colleagues) will rush to say that the two should not be pitted against each other. I accept that there is no necessary zero sum gain; but the imbalance stands to be corrected.

Why should HE students be funded at twice the rate of their FE equivalents? FE caters for a poorer student population, who generally have less in the way of family support as well as qualifications and money.

There’s a further wrinkle. HE students now take out big loans, paying £9K fees to universities, who are now cash-rich. Mostly, university graduates will go on to earn higher incomes, and pay back the loans. That’s the theory, and some of the public money lent out will come back (though not nearly as much as the government originally said). But it’s much less likely to come back from graduates with low skills. So the public purse is particularly being used to support the graduates with low skills. I’m all in favour, – very much so – of supporting people with low skills; but the finance for this does not need to go on high fees for university study. It seems to me unarguable that many of these would be far better off in a college – especially if that college were more adequately funded to give them the support they need.

One other item from the OECD report:

“Over the period 2011-13 the number of staff receiving training increased, but overall spending declined (UK Commission for Employment and Skills, 2014). According to a 2012 survey among UK employers 27% of all the time spent on continuing vocational training2 courses was devoted to mandatory training, often related to health and safety (BIS, 2013). Such mandatory training is often common among low-skilled workers, but in it nature it may not contribute much to basic skills development. ” p79

In other words, our training effort is declining; and a significant chunk of this goes on activities which may be important (as safety is) but which don’t do much to address the issue of low skills.