The Known World

“A man does not learn very well, Mr Robbins. Women, yes, because they are used to bending with whatever wind comes along. A woman, no matter what the age, is always learning, always becoming. But a man, if you will pardon me, stops learning at fourteen or so. He shuts it all down, Mr Robbins. A log is capable of learning more than a man. To teach a man would be a battle, a war, and I would lose.”

This is Fern Elston speaking, in Edward P. Jones’ wonderfully original and informative novel about slavery, The Known World. Fern Elston is a free black woman, a teacher, and she is speaking to William Robbins, the most powerful man in Manchester County. Robbins is white, and the owner of 113 slaves, but slaves are owned by both white and black men and women. One of the pleasures and challenges of the book is coming to terms with this mixing of the usual hierarchies. (I say ‘pleasures’; all of us in the book group enjoyed the book greatly, but some of the passages detailing the fragility of black existences, including of free blacks, are hard to read.)

Robbins persuades Fern, against her voiced opinion, to take on a black adult male, Henry Townsend, as a student. Henry justifies his faith, learning fast and rising to be a plantation owner himself. (One of the most powerful scenes in the book describes him visiting his parents and reporting to them that he now himself owns a slave. His father Augustus, who fought to free his family from their slave status, takes a stick and smashes his son’s shoulder in protest.)

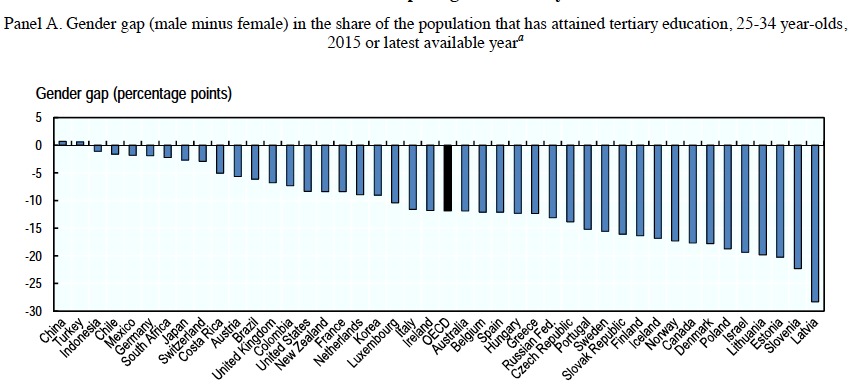

So Fern may have been proved wrong in this instance; and her stipulation of the age at which men stop learning looks a little out of kilter. But her overall sentiment was and is fairly accurate, as the evidence shows. Across all OECD countries women on average go on learning longer than men. The chart below is a little dated, but the female/male qualification gap has only got bigger since then.

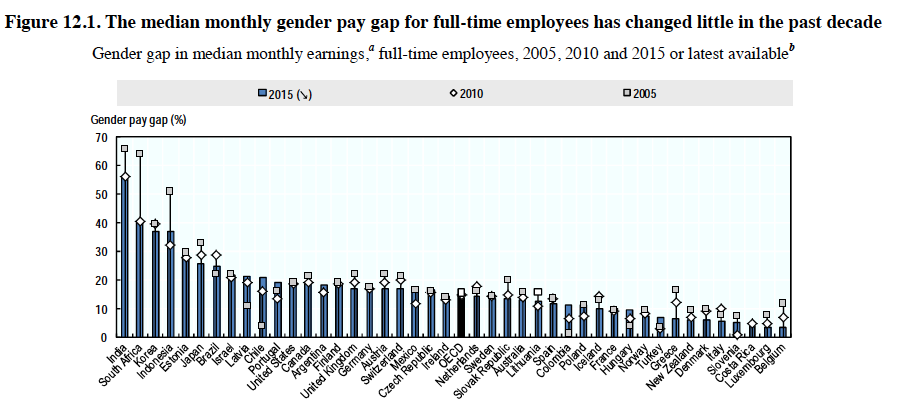

I chose this chart because it comes from a massive source of OECD information specifically on gender equality, The Pursuit of Gender Equality: An Uphill Battle, which came out three years ago but which I’ve only just discovered. It contains the Paula-relevant contrast to the chart above, namely whether the increase in women’s qualifications has been recognised and rewarded. Sadly, no. As the chart below shows, and the OECD’s title to it rightly declares, the movement towards pay parity has been very sluggish, far slower than the increasing qualification gap. And we should note that the chart refers only to full-timers; the GPG for part-timers is far greater.

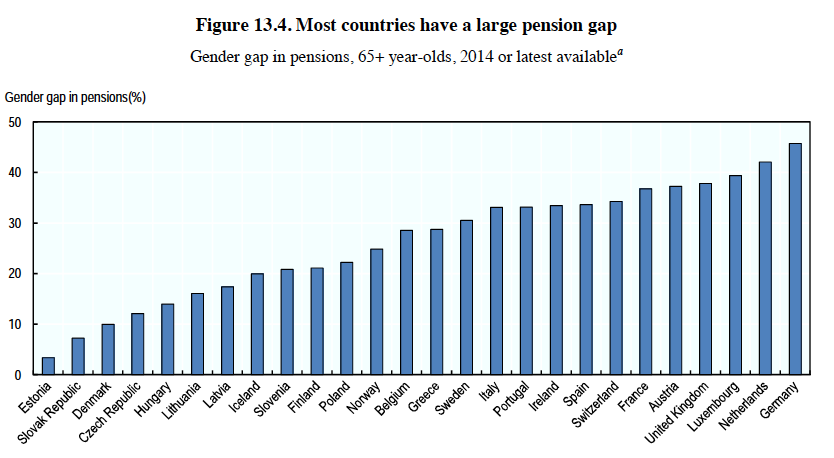

The Pursuit also includes information on the pension GPG, which is arguably the most significant of all. For the gap is large; it often lasts for decades; and there is precious little any woman can do about her pension level once it’s fixed.

Pensions were not things within Fern Elston’s purview. It would have been interesting to hear her observations on them if they had been.