The pension pay gap

By the time a woman is aged 65 to 69, her average pension wealth is £35,700, roughly a fifth of that of a man her age, according to a study at the end of 2018 conducted by the Chartered Institute of Insurance.

The emphasis is mine. It’s an amazing figure – one sex’s pension wealth at just 20% of the other’s. How does that rather abstract notion of ‘pension wealth’ translate into income difference? A recent report from the trade union Prospect (Tackling the gender pension gap) found that the gender pensions income gap (39.5%) was more than double the size of the total gender pay gap (18.5%), with the average female pensioner £7000 p.a. poorer than their male equivalent.

Both these nuggets come from The Gender Pensions Gap, a meaty report from the organisation The People’s Pension. The report is sub-titled ‘tackling the motherhood penalty, and as this implies it focusses on what having a child means for many mothers’ incomes. The recommendations are grouped into two categories: for strengthening auto-enrolment in pensions, and for improving access to childcare.

The childcare issue is very familiar (which doesn’t make it any less urgent or important). I suspect auto-enrolment is much less so. Overall, auto-enrolment is a success story, with many more women and men now achieving better levels of pensions saving because of the move to inclusion by default. But as the report makes shockingly clear, there are still many women who miss out, and who therefore experience decades of poverty in retirement.

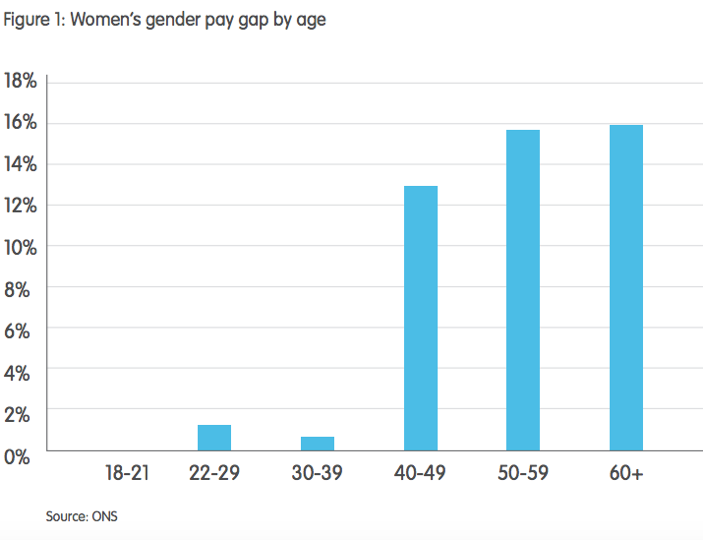

However successful the childcare reforms are, we need to think much more about the decades in between child-rearing and retirement. The table below shows how the pay gap soars in the latter half of the working life.

Improved childcare and shared parental leave, crucial though they are, will not of themselves solve this. We need a really fresh approach to careers in later life, one that embraces many different trajectories as valid, desirable and decently rewarded. We know that women’s careers can take off again in later life – more often than men’s – but this should no longer be seen as exceptional. This implies, as a minimum:

– a national careers service which is genuinely all-age, with organisations matching this with in-house careers advice for people at every stage;

– a real turnaround in attitudes to training opportunities, so that over-50s are given appropriate access to learn new skills.

– reexamination of how competences (qualifications+experience+performance) are recognised and rewarded, materially or otherwise, over the full working life.