Careers and progression

I’ve been doing a few interviews for the putative PP book, and they’ve prompted some thoughts about how different kinds of organisation do or don’t foster careers and progression. In particular, is working in a large bureaucracy more likely to help or to hinder a woman making her way up, at whatever level?

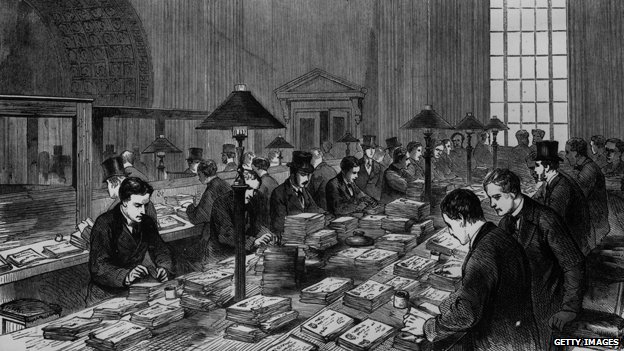

I caught some of Lucy Kellaway’s radio series, broadcast last year, on A History of Office Life. One episode dealt with the invention of the career ladder (it’s from that that I pinched the Dickensian illustration below), another with nepotism vs meritocracy. A third covered the arrival of women in the office. She slily sketches in the way office life evolved over the decades .

In principle, bureaucracy goes along with meritocracy. There are transparent rules governing such things as promotion, and this should reduce the scope for nepotism and unfairness. Everyone can understand what is required for going up the ladder, and those who make the decisions have to abide by them. This does indeed happen, and it allows leverage for making the process more fairer to all those involved. One of my conversations was with a former senior civil servant, Bella, who described how she and a colleague had changed the profile at the top of the service by a mixture of active argument (civil servants being on the whole rational folk), target-setting – with tight criteria and public accountability – and several other nudges. The combination brought about significant advancement of women through the upper ranks – though Bella was not completely sure it would be sustained.

I also listened in to several groups of women, from the central civil service and from a local authority, discussing the PP factors. I was very struck by three things. First, they were were very conscious of the gradings in the system, and of the procedures which operated for promotion between grades. This is, in one sense, what you would expect and what should happen in a bureaucracy – cf above on transparency. Secondly, though, they were alert to weaknesses in the procedures. I heard several times how ‘sponsorship’ was still needed, with ‘words in the ear’ still counting for a lot. No one spoke of nepotism, but there was a strong sense that you needed a personal backer to get that promotion, and men are more likely to have these.

Thirdly, all these women were serious about their work. They were mostly middle- or lower-grade professionals, and had no aspirations to be high-fliers. But they all wanted appropriate recognition (and reward), and to have a sense of progression. There was no torrent of complaint, but there was a general sense that the organisations they worked in were not making this happen as well as they might.

Finally, I talked to a younger woman, Ursula. Daughter of two professionals (a successful and unusual cross-race, cross-class, role-swapping marriage) she had not taken up a university place when leaving school ten years ago, but tried her luck at a musical career. In order to do that, she worked in a variety of jobs, but not just to earn money (and has now gone back to study – to Birkbeck, hurrah). So she has a track record of professional employment, but no obvious career path. I suspect, though, that she has gained experience of how to choose jobs and occupations without needing to have the steps laid out in front of her.

So one the one hand bureaucracies should favour women’s careers – and since the public sector is largely dominated by bureaucratic organisations, these are where most women work. On the other hand, women may learn to make their own paths if they follow less organised routes. It depends heavily on how competences are recognised. I’ll come back in a future post to consider whether social capital (networks) may be gaining in importance relative to human capital (qualifications and skills), and what the PP implications of that might be.