IWD: time to restart

Yesterday was International Women’s Day, and I thought this was the time to get going again on the PP blog, which I’ve neglected for months. Technology dictated otherwise, so I’m a day late…

We had the usual surge of impressive stats underlining the issues still impeding progress towards equality at work. I want to focus on just three of these.

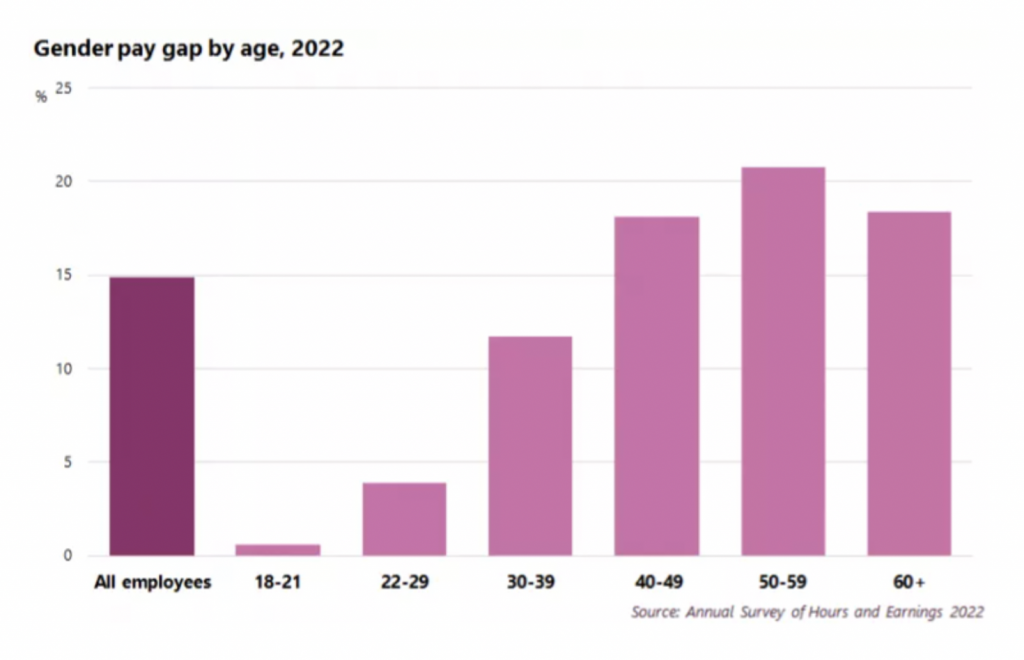

The first is the way the GPG expands hugely over the life cycle. The TUC’s excellent annual report shows this so clearly:

This is very familiar. But in recognising how this age profile has persisted over the years we need to remember that the qualifications profile by age has changed. Many women who were aged over 50 twenty years ago had not benefited from the massive upsurge in women’s education in the latter part of the C20. So although the pay gap they suffered was deplorable in itself, it was less of a meritocratic affront than it is today, when older women are ahead of older men in their educational achievements. In other words, we need to tie together historical shifts in the qualifications profile with the persistence of the way the GPG grows over the life cycle.

My second point is to do with child care. Caring responsibilities – childcare and eldercare – is Paula Factor 2, and have always been very obvious as a driver of career inequalities. But the way the UK is now underperforming on childcare has become a national shame. OECD data shows that the UK spends less than 0.1% of GDP on childcare, the second lowest investment in the OECD countries. And we now have the second highest childcare costs among leading economies. As a % of a couple’s average 2021 wage, full-time childcare is 29% in the UK; comparative figures for Netherlands, France and Japan are 13, 9 and 7. Even in the US it’s only 19%.

As a result many women drop out from paid work, either as mothers or as grandmothers or other older generation members who take on child care responsibilities. The loss to the economy of skills and competence is extraordinary, quite apart from the equity angle. Mothers who end up leaving the jobs market completely are three times more likely to return to a lower-paid or lower-responsibility role than those who do not take a break in their career. A flagrant waste of talent.

This strongly reinforces the case for a Social Guarantee. The SG’s goal is bold and simple:

“to enshrine universal services so that everyone has access to life’s essential services according to need, not ability to pay.”

Quite rightly, child care is right in the front rank of such services. I applaud the recent suggestion from a senior medic that the NHS should lead the way as an employer by providing guaranteed childcare – a win-win combining social progressiveness with a major step to alleviating the health care crisis.

Third, and closely related, is an interesting if depressing report on research by Dr Amanda Gosling of the University of Kent on the motherhood penalty. Apparently this penalty has actually increased over time for highly educated women. Highly educated mothers in 1978, ie those with some post-school education, earned about 72% of similarly qualified fathers; by 2019 this had actually dropped to 69%. This of course is in spite of the fact that the mothers were now more likely to be highly qualified than fathers (48% to 45%).

So: way to go, as they say.