Social mobility

Some familiar issues but also some progress over the last decade – these are the headlines from a useful new report by the Resolution Foundation for the Social Mobility Commission.

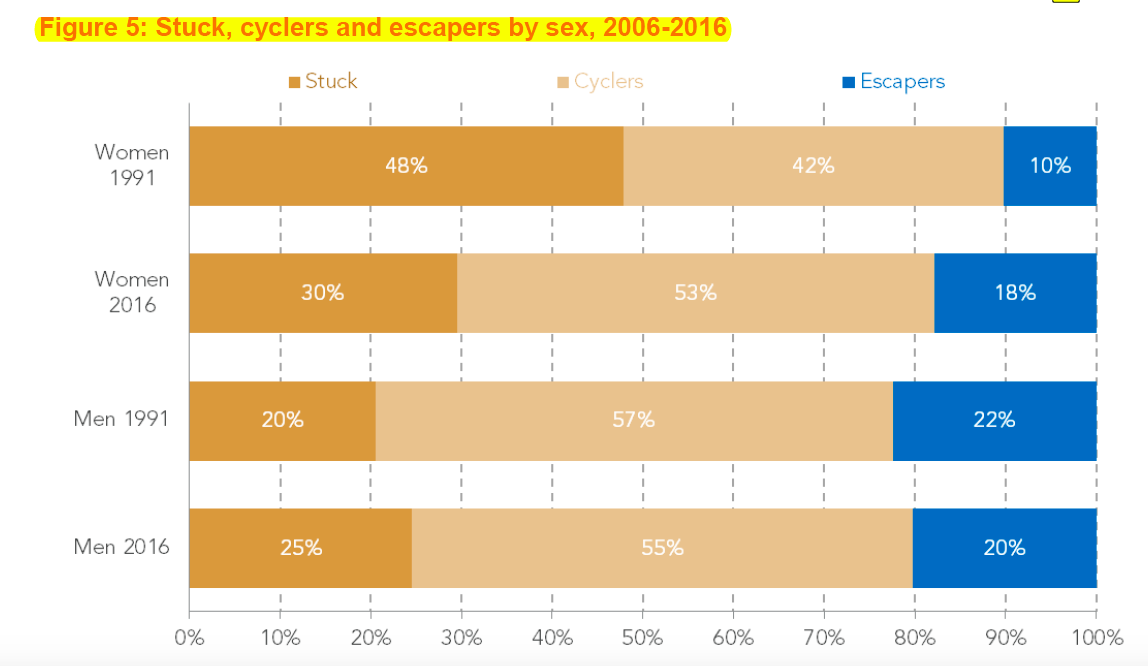

The report looks at low pay over the last decade and beyond, dividing people into 3 main groups: the stuck (who have stayed throughout in low pay, i.e. below 2/3 of the median wage); cyclers, who have moved in and out of low pay; and escapers, who have moved out of low pay and stayed there for at least the last 3 years.

Stuck is obviously where you don’t want to be. The good news is that the proportion of women who fall into this category has dropped from 48% in the decade 1981-91 to 30% in 2006-16. For men, by contrast, the ‘stuck’ figure has risen, from 20 to 25%. So the absolute numbers of stuck women have shrunk, and the basic gender gap has closed quite considerably.

The less good news is that being in part-time work is an even stronger factor than before in determining whether or not you are stuck in low pay. It is this which accounts for the increase in stuck males – i.e. more men are now working part-time. You are much more likely to escape low pay if you work full-time, and this has become more important as a factor. In the initial part of the 2006-16 decade whether you were working full- or part-time didn’t make much difference to your chances of escape. By the end of the decade over 70% of the escapers were working full-time. In other words, working part-time damages your career prospects, whether this is for professionals or, as we see here, for people at the other end of the occupational hierarchy.

The report concludes that improving the quality of part-time work is a key component of the social mobility challenge. It’s a very strong piece of work; I’d just like to see the analysis pushed further, in two respects. First a more fine-grained analysis, along exactly the same lines but going beyond the simple binary division into full-time and part-time. And secondly, but this is an even harder ask, one which took into account the fact that women’s qualifications grew throughout the decade at a faster rate than men’s.