Social mobility, occupational maturity and an early pay gap

The Social Mobility Commission’s report on the influence of social class on professional progression deservedly got wide coverage. It moves the debate along from looking only at entry into different professions, to show how people from different social origins do or do not make progress and are or are not rewarded once they have been working for a while. The analysis shows that those who come themselves from the lower social classes earn on average £6800 less – 17% – than their peers who themselves originate from the professional classes.

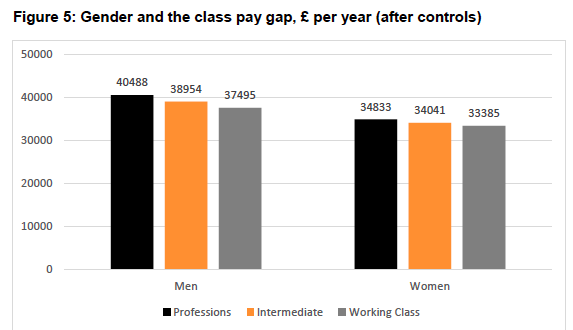

The class gap is bigger for men than for women. But the report points out that there is a double disadvantage, so that women from working-class backgrounds earn 21% less than men from professional backgrounds in the same occupational group.

The authors – Sam Friedman, Daniel Laurison and Lindsey Macmillan – go on to identify a number of factors which explain this. Not surprisingly, they overlap very much with the PP factors: reluctance to ask for pay rises, less access to social networks, discrimination (conscious or unconscious) and ‘cultural matching’.

It’s valuable work, which shows once again the value of longitudinal analysis that tracks people over time. I found one side reference particularly thought-provoking. It’s to the notion of ‘occupational maturity’. Erszebet Bukodi and her colleagues use this term to describe the stage at which most professional individuals reach the point where their careers are established. This is currently around their mid-thirties. It made me wonder how far this reflects a particular gendered view. The term itself is descriptive of how things are, and I’m sure is accurate in that respect. But it carries with it a normative charge. Of course it doesn’t suggest that if you haven’t made it by your mid-thirties you’re not going to make it all; but it reinforces a particular sense of what a career trajectory looks like. So women who resume a career, or put on a later spurt for whatever reason, may find it harder. This makes less and less sense in a context of extended working lives.

Looking the other way, to childhood, the Guardian reports on analysis by Childwise (but sorry folks, I can’t provide a link – Childwise is a market research agency, so their surveys cost £1800) which reveals a gender pay gap in pocket money and pay given for domestic tasks. Boys aged 5-16 get an average of £10.70 from this source, and girls £8.50. For the age group 11-16 the gap is 30%. Just as significantly (to me), boys are more likely to be paid regularly in cash, whereas girls get things bought for them (though these things may be more expensive than items bought for boys). I wonder how conscious parents are of this? I suppose they might not be at all conscious where they have kids of only one sex; but it would be interesting to know how far discrimination starts within households with children of both genders.