Transparency and audit, plus OECD on gender and skills

Yesterday I attended a TUC conference on AI – a lot to take in, some of it quite frightening. The TUC has been doing excellent work on the challenges AI presents in the workplace. One of the speakers was Robin Allen, a KC who has long experience of legal issues to do with equality. I spoke to him briefly at the end as he’d referred to the Gender Pay Gap in his remarks. To my surprise he was dismissive of the GPG transparency moves. Robin’s view is that only pay audits which reveal what men are paid will have an impact.

I’m not convinced; for one thing the obligation (on big companies) to publish GPG data gives us the opportunity to ask sharper questions at companies AGMs, as ShareAction does so assiduously.

Publishing this kind of data is also one of the recommendations in another solid report from OECD on gender, education and skills. Unsurprisingly it confirms the Paula Principle line of argument, namely that women increasingly outperform men educationally but do not see this reflected in their pay and careers. Here’s what the report concludes:

“Reflecting on the stubborn persistence of gender pay gaps, national measures should be introduced to reduce wage disparities between men and women. One effective policy measure involves pay transparency, which makes companies acknowledge the size of their gender pay gap. Companies are increasingly required to carry out analyses of gender wage gaps, and are requested or required to share this information with employees, government auditors or the public. Other new strategies include introducing pay-gap calculators, which are often publicly available on line, as well as certifications for companies showing best practice in gender pay equality. These types of measures have been proposed or introduced in several countries since 2013, including Australia, Japan, Germany, Lithuania, Sweden, Switzerland and the United Kingdom.”

The OECD report focuses heavily on subject choice:

“Analysing data from both 2005 and 2020, it is striking that women’s field-of-study choices have not changed over time… The percentage of new female tertiary graduates in engineering, manufacturing and construction remained almost the same at around 25% in the 14 years between 2005 and 2020, and it shrunk by about 4% for female graduates in ICT-related fields. In contrast, the percentage of female graduates in fields related to education (80%), health (80%) and social sciences (70%) has hardly changed since 2005.”

Quite rightly, the authors then discuss what might be done to correct the subject choice imbalance. Behind this issue there is a wealth of PP-relevant data. The first is a chart clearly marking the overall crossover point in those without an upper secondary qualification:

The 2015 crossover date may seem surprisingly late and the differences small. but remember this is for the entire 20-65 populations, so the balance will shift only gradually, as new entrants into this age group (where women will be markedly better qualified) are only a small proportion of the total. it’s another reminder of the need to look across the full life course.

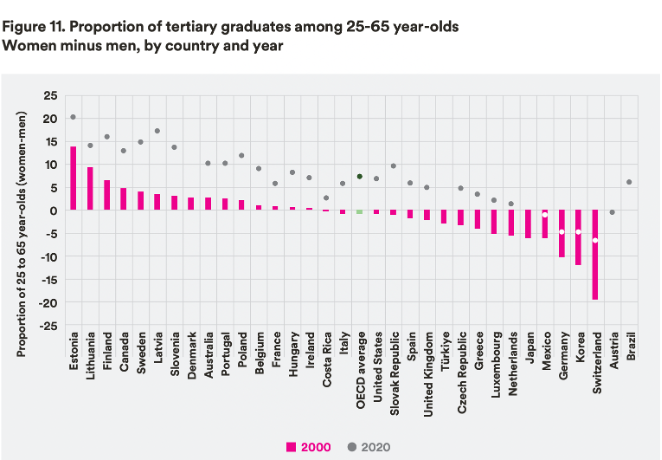

If we look at tertiary qualifications the change in country profiles is clear:

Even in those countries – notably Switzerland – where man graduates still outnumber women (again, in the population as a whole), the direction of change is very clear, as the dots show.

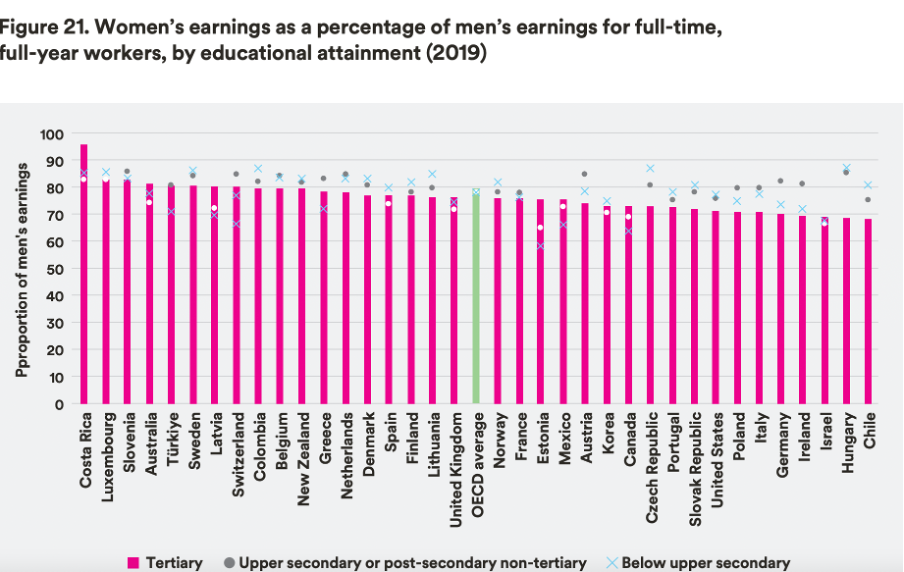

But now look at the earnings side:

Good on Costa Rica. But note that this refers only to full-timers, and that on average across OECD countries, women are about twice as likely as men to work part time or part year, regardless of their educational attainment.

To conclude on the brighter side it’s worth noting that women gain more from men by moving up to graduate qualifications. In other words, graduate women do better relative to non-graduate women than graduate men do to non-graduate men:

“On average across OECD countries, 25-34 year-old tertiary-educated women earn 52% more than women of the same age with only an upper secondary education do. In contrast, the earnings premium related to a tertiary degree among young men is 39%.”