Updates on gaps and crossovers

It’s that time of year again: results, results and more results. So:

For SATS taken by around 600,000 10- and 11-year-olds, I’ll let the official DfE announcement speak:

“Girls continue to outperform boys across all subjects at the expected standard. In 2019, 70% of girls reached the expected standard in reading, writing and maths (combined) compared to 60% of boys, a gender gap of 10 percentage points, up from 8pp in 2018. This has been driven by an increase in the gender gap in reading, where both boys and girls saw a fall in the proportion reaching the expected standard between 2018 and 2019, but the fall was higher for boys (down 3pp to 69%) than girls (down 1pp to 78%).”

Now for the other end of the initial education system, and high level university qualifications, ie first or upper second class degrees. We had another crossover in 2016/17 as women overtook men in the proportions getting first class degrees (26% to 25%). This was confirmed this year (28:27). And of course since there are far more women in universities, these proportions disguise a large absolute figure, of over 18000 (64.5K : 46K). When you add in upper seconds, the gap expands enormously, so that there are over 64000 more women graduating with good degrees.

I put that last figure in bold because the debate on ‘equality’ so often ignores the extent to which girls and women outperform boys and men educationally. This should a) give added urgency to the debate on how such qualifications are recognised and rewarded in the workplace; and b) make us think again about 50:50 targets. When women do so much better, just how appropriate are these?

Which takes us to what happens in the workplace. At Common Vision’s Millennifest meeting last weekend I was an imposter – not having read the blurb (duh) I didn’t realise that the event was for millennials, and so was the oldest participant by some 30 years. Happily I was not made to feel too weird. Julia Valentine of the Women’s Equality Party ran the workshop on parity in the workplace and we had a most stimulating discussion. It ran from why women are heavily represented in marketing to why men feel shame if they don’t exhibit upward striving. Gender Pay Gap reporting entered the conversation – which takes me to my last set of figures.

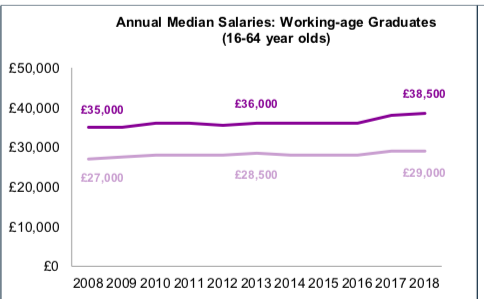

We’ve seen above how far ahead women are in qualifications, and how the gap is increasing. It’s the contrast between this fast-increasing female-female gap and the only-slowly-shrinking male-female pay-and-career gap that forms the essence of the Paula Principle. So here are recent data on graduate pay from the DfE’s Graduate Labour Market Statistics:

The gender gap was £8K in 2008/9 – and £9.5K ten years later. That’s mainly because of what happens in decades 3-5 of people’s working lives – at least at the professional level, women and men start off fairly equal, but the gap grows rapidly after about 15 years. Of course there’s an inevitable lag as better qualified women move through the decades, so equalisation of median levels in older age groups will take time. But it’s hard to see that the rate of change in career rewards remotely matches the changes in competences.

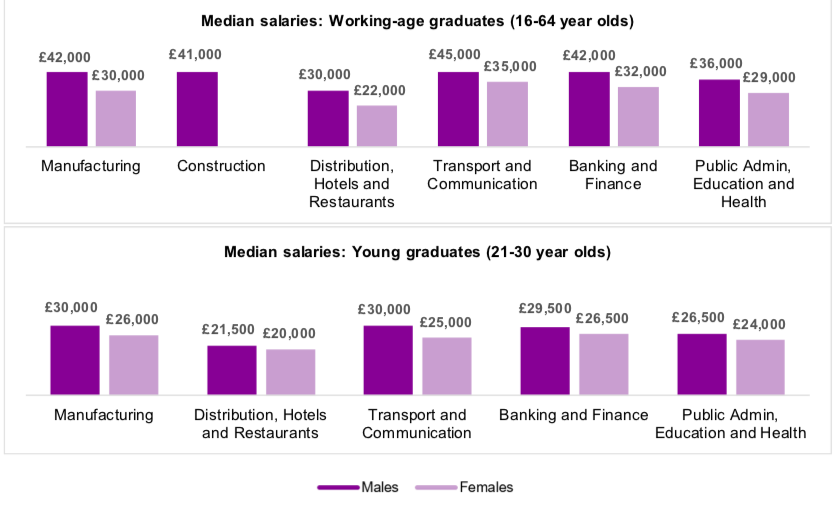

As a last data titbit here are the sectoral differences, from the same source. The Paula Principle operates very variably, across sectors and organisations, so it’s important to see the differences. The biggest gap, predictably, is in banking and finance – not for young graduates, but the full working life. As I’ve often pleaded before, we need rigorous reviews of what ‘careers’ can look like, sector by sector, organisation by organisation.